_This is my qualitative review of a 6 week period from 20 September until 31 October._

Amble 3 was: three weeks of study, two weeks of "special projects" and one week focussed on meetings, a conference and life admin. I also did 5.5 days of advisory work for 80,000 Hours.

## New blog!

Working title: [Sunglasses, Ideally](https://sun.pjh.is).

Marginal Revolution-style—one post every day _no matter what_. Often [quotes](https://sun.pjh.is/tagged/quote), sometimes my own [writing](https://sun.pjh.is/tagged/writing).

For now I see this as a study journal rather than something meant for an audience. It's an experiment. So far, I like it.

The blog experiment runs alongside a new morning routine: at least 30 mins of open writing, then 30-90 mins of writing/reading every day, _no matter what_.

This is part of my attempt to find [better ways to train](https://notes.andymatuschak.org/zxiCQhASjT1JsURvLj29akQ4taJyX34RDUhG?stackedNotes=z4qhD8UwNAmJDdJUC36BUGp5PEUfgfzZXvkhB).

## Cold Takes

I spent a couple days re-reading and reflecting on [Cold Takes](https://cold-takes.com), the blog of [[Holden Karnofsky]].

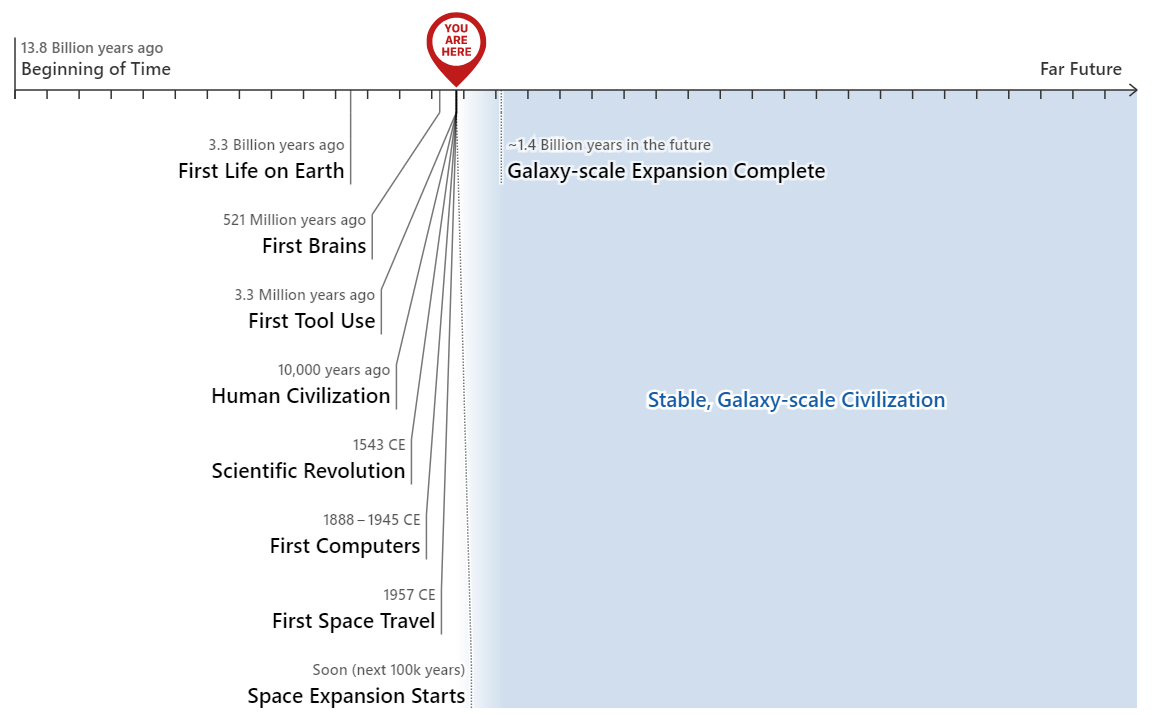

Like [[=Robin Hanson]], Holden starts his story by zooming out on the history of the universe, and remarking that the current moment looks pretty wild:

Quite a lot has happened in the ~pixel that represents the last ~3 million years. As he puts it:

> - The last few millions of years - with the start of our species - have been more eventful than the previous several billion. The last few hundred years have been more eventful than the previous several million. If we see another accelerator (as I think AI could be), the next few decades could be the most eventful of all.

We usually think on the timescales of a few years, perhaps a decade or two, perhaps even a century or two. This makes our current era seem normal, when in fact it is extremely remarkable:

The "long view" perspective gives a counterweight to the default "nothing new under the sun" prior, which makes most people (reasonably) suspicious of novel, radical claims about the future.

If we want to think about technological progress more than a few years out, most of us will need to down-regulate our "epistemic immune system"—increase our tolerance for weird and wild claims, engage our system 2, recognise that our intuitions are not a reliable guide. The "let's take a long view" opening is an invitation to do this.

It's tempting to combine a concession that "the longrun future will be radically unfamiliar" with the thought that (thankfully) the longrun future is a long way off.

The central claim of Holden's series is that the longrun future may be coming soon.

In short:

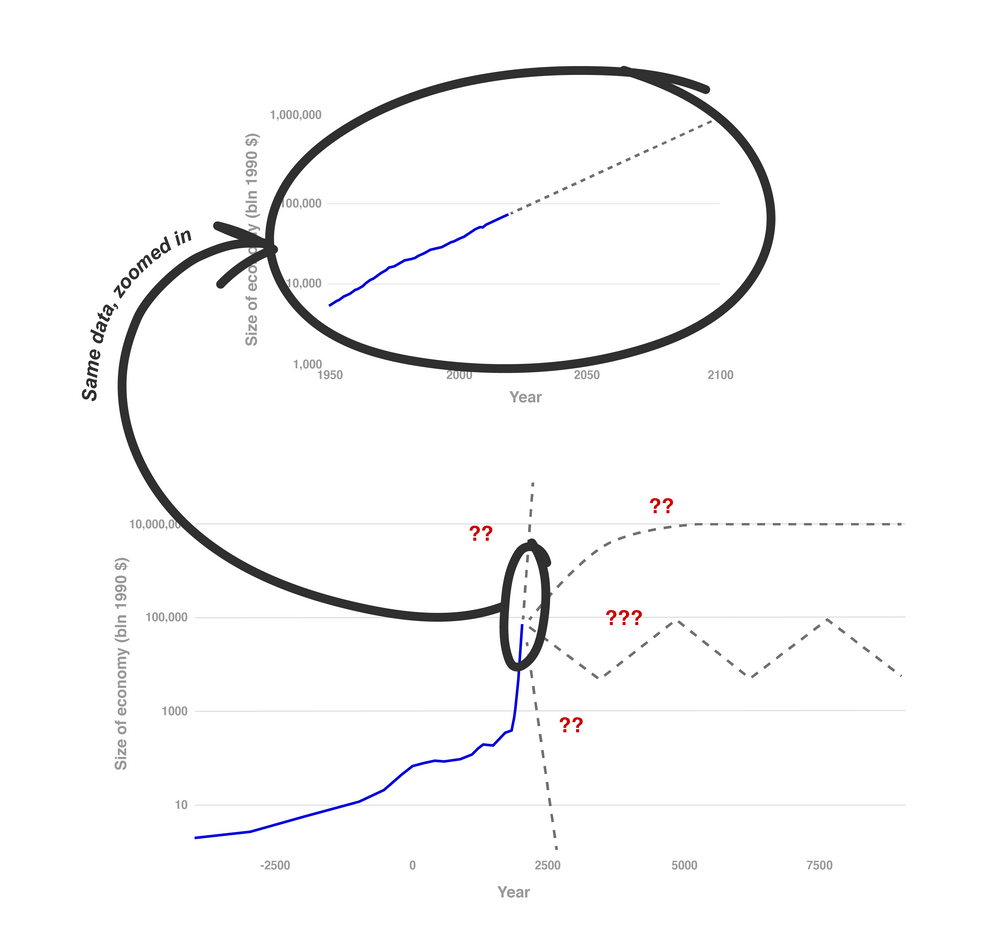

1. If we could develop a process for automating scientific and technological advancement (PASTA), then the world economy would enter a new, much faster growth phase.

2. The best available AI timelines suggest that we will develop PASTA-type capabilities by the end of the century.

(1) might sound rather speculative, but there are reasons to think this is the "default" scenario, i.e. you can see it as a continuation of past trends.

I have not dug deep into (1) or (2). My views in this area, such as they are, are something like:

(a) Yep, AI is a strong candidate for the most important technology we develop this century.

(b) Yep, PASTA within 100 years seems plausible.

(c) Yep, our best models of economic growth suggest PASTA would cause an increase in the growth rate which humans would perceive as explosive.

(d) Yep, the effects of PASTA / increasingly powerful AI seem hard to predict, and could be very good or very bad.

(e) Yep, this seems quite urgent, i.e. hard to put less than 10% that it'll arrive within 20 years, hard to put <50% on arrival before 2100.

(f) I don't know what we should do about (a)-(e).

Many norms and institutions seem unduly risk-averse, yet many others seem scarily risk-oblivious. There's a tricky needle to thread—promoting awareness of risk, without triggering a harmful overreaction. The history of nuclear power seems like a cautionary tale.

I hosted an [Interintellect Salon](https://interintellect.com/salon/high-stakes-fragile-porcelain-is-this-the-most-important-century/) to discuss this material. The event went fine, but it was less succesful than [my first salon](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E-uSDlbSXjw). I deliberately spent less time on prep, but this meant I didn't do a great job on selecting required reading and providing a supporting structure for the group discussion. I also felt unusually tired and sluggish during the event, despite being well-rested. My takeaway: prep more and prefer smaller groups.

## Cold Takes (Meta)

In his [interview with Ezra Klein](https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/05/podcasts/transcript-ezra-klein-interviews-holden-karnofsky.html), Holden remarks:

> At Open Philanthropy, we like to consider very hard-core theoretical arguments, try to pull the insight from them, and then do our compromising after that.

The "hardcore theory" gets you the generativity of principled, model-based thought, and the compromise step puts the models "back in their place" as just one perspective among many.

This movement encourages us away from a dogmatic "my favourite theory" approach and towards what [[Tyler Cowen]] sometimes calls "[[Epistemological hovering]]": a disposition to continually consider things from different perspectives, and seek the insight in each.

My guess is that a deep-rooted commitment to perspectivism makes us more robust to out-of-model error, and less likely to become harmful fanatics.

Importantly, the message isn't just "try many models". It's "try many models, then compromise". With Holden, I share the hunch that this "compromise" step is very important, yet very difficult to formalise:

> And so, what I believe in doing and what I like to do is to really deeply understand theoretical frameworks that can offer insight, that can open my mind, that I think give me the best shot I’m ever going to have at being ahead of the curve on ethics, at being someone whose decisions look good in hindsight instead of just following the norms of my time, which might look horrible and monstrous in hindsight. But I have limits to everything.

>

> I also just want to endorse the meta principle of just saying, it’s OK to have a limit. It’s OK to stop. It’s a reflective equilibrium game. So what I try to do is I try to entertain these rigorous philosophical frameworks. And sometimes it leads to me really changing my mind about something by really reflecting on, hey, if I did have to have a number on caring about animals versus caring about humans, what would it be?

>

> And just thinking about that, I’ve just kind of come around to thinking, I don’t know what the number is, but I know that the way animals are treated on factory farms is just inexcusable. And it’s just brought my attention to that. So I land on a lot of things that I end up being glad I thought about. And I think it helps widen my thinking, open my mind, make me more able to have unconventional thoughts. But it’s also OK to just draw a line […] and say, that’s too much. I’m not convinced. I’m not going there. And that’s something I do every day.

This spirit informs the "[worldview diversification](https://www.openphilanthropy.org/blog/worldview-diversification)" strategy taken by Open Philanthropy. I had several interesting conversations about this strategy during the amble—it turns out to be more controversial than I would have guessed.

Detractors tend to mutter things like "idiosyncratic" and "arational commitment to moderation", or mention formal models as evidence against a strategy that optimises across multiple variables. One detractor objected that paying for robustness is a concession to egoism.

I really want to understand the views of the "detractors" more deeply. My hunch is that they're wrong, but I want to get clearer on the cruxes. I think it may come down to standard progressive-conservative differences, i.e.

1. How much to trust explicit reasoning vs intuitions/traditions/norms that have survived selection pressure.

2. How much to focus on self-preservation (robustness; lots of what we have now is good) vs self-transformation (optimisation; what we have now is mostly bad).

## Nietzsche, Parfit, Sidgwick

Most of of my study this period was about preparing for a return to Nietzsche and, in particular, a return to the question of how to think about ethics in light of secular, naturalistic psychology. And—at the same time, to give the rationalist-intuitionist theories of Sidgwick and Parfit the most sympathetic hearing I can muster.

I found Andrew Huddlestone's "Nietzsche and The Hope Of Normative Convergence" to be a good commentary on Parfit's discussion of Nietzsche—in particular, the ways that Nietzsche threatens Parfit's intuitionist moral epistemology, and the ways that Parfit underestimates that threat. I summarised my takeaways [here](https://sun.pjh.is/nietzsche-wasn-t-climbing-parfit-s-mountain).

It is striking that Parfit quotes Nietzsche in the dedication of _Reasons and Persons_. Parfit regards Nietzsche as one of the great moral philosophers, yet his methods and metaethics seem strongly in tension with Nietzsche's most famous arguments. Are there grounds for a Straussian reading of Parfit's work, where he concedes rather more to Nietzsche than might first appear? I am looking into this. Several people have told me contradictory versions of a story where Parfit loved either the quote, or his photo of Venice (which appears on the cover), and used one to justify the other. I find it hard to believe that either of these is anything like the full story.

## Richard Rorty on Bernard Williams

I came accross a [great review](https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v24/n21/richard-rorty/to-the-sunlit-uplands) of Bernard Williams' book _Truth and Truthfulness_. In it, Rorty casts Williams as trying to concede a lot to Nietzsche—but not too much.

> He needs carefully to distinguish between justified Nietzschean and Foucauldian suspicions about the supporting stories, and unjustified contempt for the Enlightenment’s political hopes. In making this distinction, he takes on the same complicated and delicate assignment previously attempted by Dewey, Weber and many others. He wants to show us how to combine Nietzschean intellectual honesty and maturity with political liberalism—to keep on striving for liberty, equality and fraternity in a totally disenchanted, completely de-Platonised intellectual world.

>

> The prospect of such a world would have appalled Kant, whose defence of the French Revolution was closely linked to [what Williams criticised as] his ‘rationalistic theory of rationality’. Kant is the philosopher to whom such contemporary liberals as Rawls and Habermas ask us to remain faithful. Williams, by contrast, turns his back on Kant. So did Dewey. The similarity between Dewey’s and Williams’s conceptions of the desirable self-image for heirs of the Enlightenment is, in fact, very great, so I am all the more puzzled by his hostility to pragmatism...

During the review, Rorty brings out many of the attractions of pragmatism, and the way that the story you tell about reason is central to the story you tell about philosophers.

My highlights [here](https://sun.pjh.is/richard-rorty-reviews-truth-and-truthfulness-by-bernard-williams).

Just as I want to better understand why Parfit found Williams' views so disturbing, I want to better understand why Williams found Rorty's pragmatism worth resisting.

Williams on Rorty, [13 years earlier](https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v11/n22/bernard-williams/getting-it-right):

> If the Enlightenment tended to see the paradigm of understanding as scientific knowledge, and society as a machine—in fact, it did not uniformly do either—we do not have to follow it in that. There may be other and more serviceable ways of describing liberalism and helping to save it.

>

> Rorty’s own way of approaching this very real problem takes the cavalier form of trying to do without the peculiar concerns of truth at all, scientific or any other. He also expresses his aim in terms of exchanging for the ‘rationalisation’ of society its ‘poeticisation’: a form of self-consciousness about the contingency of its guiding metaphors.

Williams thinks that Enlightenment liberalism is founded on the idea that there is a form of persuasion that is not based on force, but rather a shared, consensual pursuit of truth. If, as Rorty would have it, justification is merely about "what others will let us get away with", and not about "getting it right", something critical is lost. But what, exactly? Was Williams also looking for a story that involves convergence towards a transcendent standard—despite his atheism, his historicism, his Humean picture of rationality? I had better read more...

I emailed the authors of the [Stanford Encylopedia article](https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/williams-bernard/) on Bernard Williams, suggesting they add [Rorty's review](https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v24/n21/richard-rorty/to-the-sunlit-uplands) to the secondary sources list. To my surprise, they replied quickly, thanked me for the tip, and promised to add it in the next revision.

## Radical uncertainty, animal spirits and Nervous Nellies

I went back to King and Kay's book, _Radical Uncertainty_, and wrote a [grumpy blog post](https://sun.pjh.is/tetlock-vs-king-and-kay-on-probabilistic-reasoning) about it. I still feel like there are some important insights in their work, but also that I don't fully understand their views, and that they present them badly.

John Vervaeke tells a story where [relevance realisation](https://sun.pjh.is/john-vervaeke-on-rationality-relevance-realisation-and-insight) is at the heart of cognition.

> You have to shift away from a framing of decision theory or quantitative analysis, because the fundamental problem is overcoming an ill-defined problem to generate a well-posed problem—and _then_ you can have a numerical analysis.

I wonder if a central reason that King and Kay want to dunk on probabilistic reasoning is that they think it obscures the deeper challenge of posing the problem (in their terms: "constructing a reference narrative").

There's also Keynes on the limits of (uncomputable) decision theory in practice:

> Human decisions affecting the future, whether personal or political or economic, cannot depend on strict mathematical expectation, since the basis for making such calculations does not exist; and that it is our innate urge to activity which makes the wheels go round, our rational selves choosing between the alternatives as best we are able, calculating where we can, but often falling back for our motive on whim or sentiment or chance.

>

> [...]

>

> a large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than mathematical expectations, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits—a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.

And Tyler Cowen on [builders vs Nervous Nellies](https://sun.pjh.is/tyler-cowen-on-builders-vs-nervous-nellies):

> Uncertainty should not paralyse you: try to do your best, pursue maximum expected value, just avoid the moral nervousness, be a little Straussian about it. Like here's a rule on average it's a good rule we're all gonna follow it. Bravo move on to the next thing. Be a builder.

>

> So… get on with it?

>

> Yes ultimately the Nervous Nellies, they're not philosophically sophisticated, they're over indulging their own neuroticism, when you get right down to it. So it's not like there's some brute let's be a builder view and then there's some deeper wisdom that the real philosophers persue. It's you be a builder or a Nervous Nelly, you take your pick, I say be a builder.

I sent this quote to Joseph Walker, whose tweet made it to [Tuesday assorted links](https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2021/10/tuesday-assorted-links-338.html).

## Shameless psychologising

My inclination to psychologise thinkers who have a taste for monistic theories of value and Kantian theories of rationality (as opposed to pluralism and particularism) continues unabated. My desire to go deeper on these topics, and to train harder in formal reasoning, is also growing.

I went back to Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek [being admirably honest](https://sun.pjh.is/katarzyna-de-lazari-radek-on-the-attractions-of-monistic-hedonism) about the motivation for her hedonism:

> I don’t like dilemmas, I want to overcome them. I feel that there must be a guidance. Maybe there is this desire in me to find a proper guidance, and I worry that with pluralistic theories, its impossible, or maybe you need to end up with particularism, i.e. a pluralistic theory where you need to decide _every time_ what to do.

And John Dewey, psychologising the moralists:

> Ready-made rules available at a moment’s notice for settling any kind of moral difficulty and resolving every species of moral doubt have been the chief object of the ambition of moralists. In the much less complicated and less changing matters of bodily health such pretensions are known as quackery. But in morals a hankering for certainty, born of timidity and nourished by love of authoritative prestige, has led to the idea that absence of immutably fixed and universally applicable ready-made principles is equivalent to moral chaos.

It's tricky: I do think there is lots to be gained from seriously entertaining a theory that we know is too simple to be correct. Perhaps I just want it to be done a little more in the spirit that Holden describes, above.

## Special projects

For 80,000 Hours, I drafted a blog post called [[§Career advice for under 30s]]. A Hartree-flavoured attempt at an "introduction to social impact career advice". The aim was to generate internal discussion, and hopefully feed an idea or two into Ben's next draft. It was a success on both counts. To my surprise, Ben encouraged me to turn the draft into an EA Forum post. I will probably do this during my next amble.

I also began work on a "surgical strike" to improve the website of Joseph Walker's podcast. The project is going well, but the timeline is much delayed due to some issues on his side. We will finish during November.

## Salons

I attended three Interintellect salons:

- [[=Luke Burgis]] on [[=René Girard]]—his book is a readable introduction.

- [[=Nigel Warburton]] on public philosophy—some notes [here](https://sun.pjh.is/notes-on-public-philosophy).

- [[=Pamela Hobart]] on clarity—it got me back to [Nietzsche](https://sun.pjh.is/nietzsche-on-love-of-truth-life-and-perhaps-even-cultivating-the-species). And I found myself characterising clarity as "that feeling you get when the decision is made, and it's time to act".

## London visit and conference

I spent a week in London, visiting the 80,000 Hours office in the run up to the Effective Altruism Global conference.

I decided to (mostly) continue working as usual in the mornings and go slowly on meetings, networking and socialising. I aimed for (and slightly exceeded) about 2 substantive 1-1 meetings per day, about half of which were with people I had not met before. Several memorable conversations, a couple of new connections that may be interesting. I also did a walk and meeting with a potential hire for 80,000 Hours. I'm happy with how the week went.

## Progress against stated goals

I hit most of the targets I set in my plan.

The biggest and most serious "miss" was writing an EA Forum post. That was due to me making less progress than I would have liked on the [[>Psychology vs moral philosophy]] project. The reason for this was that I put less time into it than I planned. This, in turn, was caused by the two "special projects" I worked on—one ran to the upper end of the time I had allocated, and one exceeded it. When planning the amble, I considered cutting one of the projects due to this foreseeable risk, and decided against. I think it was a fine decision, but it's a reminder of the value of focus—one "special project" is fine, but two is too many. Starting [Sunglasses, Ideally](https://sun.pjh.is) was, in part, a reaction to the recognition that time was getting away from me.

I had a big list of life admin tasks to clear during this period, and I'm very happy with the rate of progress. Still a couple of important things I'm not quite "on top" of—I'll schedule another day or two sometime soon to clear the backlog.

## Personal life

My last amble was heavy on personal stuff and light on ideas. I'm not sure if that's an objection, but this time I've tried to avoid this by leaving "personal" stuff for last. Actually I've left it so late that I'm really out of steam. So I will just say: I had a wonderful month in Reykjavík, spending time with dear friends and places, and getting to know some familiar faces a little better. Now I'm back in France, getting setup for the winter. And, most immediately, the opening of the Penne d'Agenais Coworking & Bridge Unit, which will host its first guests next week.

My [music blog](https://mtv.pjh.is/) is now on pause.

## Closing remarks

Overall, I'd say: 8/10. Good. Promising. Onwards.